Photo credit: Medium

Composers are often presented as superheroes in the context of history—geniuses that kicked doors down, took names, and made music solely on their own terms, composers like Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven. But even the most legendary of composers enjoyed having a helping hand every once in a while. In honor of International Friendship Day on August 5, here’s just a few examples of times when history’s greatest solo acts grabbed a buddy to create music that would echo throughout the generations.

Mozart & Salieri — Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia (1785)

Salieri did not murder Mozart, but one thing that the jury was out on until recently was if the two rival composers were ever really friendly. That was until the long-lost piece, Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia was accidentally unearthed in late 2015—music that was actually co-written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri.

The piece also features a third, unknown composer. Listed under the single name of Cornetti, it is likely to have been a student of Salieri’s. Photo credit: Il Corriere Musicale.

This cantata, translated as For the recovered health of Ophelia, was composed to celebrate the professional return of the opera star Anna Selina “Nancy” Storace, whose voice had suffered a catastrophic failure in June of 1785. Storace was a favorite collaborator and muse to both Salieri and Mozart.

Although there were records of Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia’s existence in Viennese newspapers, no copies of its text or sheet music had ever been found, bestowing a mythical status to the music. That was until the piece was rediscovered by musicologist and composer Timo Jouko Herrmann.

While perusing the Czech Museum of Music’s online database, Herrmann, a Salieri scholar familiar with the piece’s importance, discovered something impossible: Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia had been archived and even labeled in the museum’s catalog for over 40 years—and no one had ever noticed. The group of materials that contained Per la ricuperata salute di Ophelia was added to the museum’s collection back in the 1950s and was even properly labeled in the 1970s, but since the names of the composers were coded using pseudonyms and abbreviations, its true historical value remained unnoticed for years.

University of Texas alumnus F. Murray Abraham’s portrayal of Antonio Salieri in Amadeus has long cast an image of the composer as a jealous, murderous rival in popular culture. Photo credit: The Film Spectrum.

While the piece doesn’t exactly prove Salieri’s undying love for Mozart, it does confirm that besides being competing musicians, the two shared at least a partially amicable relationship. Though, you might be a little disappointed to hear that the piece is, in the astute words of Mozart expert Ulrich Leisinger, “not that great.”

Debussy & Satie — Gymnopédies Nos. 1 & 3 (1898 ver.)

In a musical era of pompousness, high regard for tradition, and love for all things Germanic, French composers Erik Satie and Claude Debussy found plenty to bond over. Debussy, with his impressionistic style, made music that was unprecedented in its lack of traditional forms and sounds. Similarly, Satie was a composer that did as he wanted and openly insulted anyone who displeased him. Though Debussy wasn’t as extreme as Satie in this regard, the two were as thick as thieves and would frequently go out on walks, smoke together, and talk music.

In pieces like Embryon’s desséchés, Satie would quote passages and publicly mock the music of Beethoven, Wagner, and Chopin. Photo credit: Wikipedia.

Satie published the first version of his Gymnopédies in 1888. Although the Gymnopédies is a classic by today’s standards, it was contradictory to the spirit of its age when first published. Back then, piano sets were composed for the purpose of variety in key, tempo, color, and expressiveness. Gymnopédies defied these romantic expectations by being almost anti-virtuosic. The three-piece composition was set all in the same slow tempo, same time signature, and featured nearly identical melodic rhythms.

Satie loved to write tongue-in-cheek remarks in his scores. Photo credit: Rebloggy

During one of their many hangout sessions, Debussy and Satie visited fellow composer Gustave Doret at his home. Satie had brought Doret a deluxe edition of his Gymnopédies and began to play them at the piano, poorly. Debussy then stepped in and said, “Come on, I’ll show you what your music sounds like.” After performing beautifully and giving it the passionate color that Debussy was known for, Doret said, “The next thing is to orchestrate it like that.” Debussy responded, “If Satie doesn’t object, I’ll get down to it tomorrow.” Satie whole-heartedly agreed.

In orchestrating the Gymnopédies, Debussy changed very little compositionally, but his well-known coloristic talents resulted in a version of the piece that was all his own. Although Debussy’s championing of the Gymnopédies successfully popularized the piece, Satie never gained much success in his lifetime and lived the rest of his days in relative poverty.

Hildegard of Bingen & Richardis of Stade — Ordo Virtutum (c. 1151)

Hildegard of Bingen became a musical legend in the 12th century by using her self-described visions to compose text and music. And while Hildegard’s compositions were some of the best in all of liturgy, they weren’t all necessarily about god.

One of the most important composers of the 12th century, Hildegard had barely started composing by the age of 38. Photo credit: Classical MPR

Ordo Virtutum (Order of the Virtues) is one of Hildegard’s most celebrated musical works, as well as one of the first known morality plays in the history of music. The piece was first debuted in an unfinished form in Hildegard’s illustrated work Scivias in 1151, which was written with the help of her confidant and closest friend, the nun Richardis of Stade.

Unfortunately, their friendship had an expiration date. One day, apropos of nothing, Richardis was transferred to a monastery in Bassum under the direction of her brother Archbishop Hartwig of Bremen, far north of Hildegard’s convent in Rupertsberg. Whether or not it was Richardis’ decision to leave Rupertsberg is unclear—in a letter to Hartwig, Hildegard describes Richardis as being unjustly “dragged” away from her convent. Richardis’ new position at Bremen came with a suspiciously large promotion as well, to the position of Abbess. This perturbed Hildegard, as she suspected Hartwig of nepotism and corruption.

Hildegard was heartbroken and betrayed, and appealed to every connection she had in the church, even the Pope himself, in order to have Richardis brought back home. Hildegard’s attempts to circumvent the bureaucracy of the church failed, and Richardis stayed at her new post in Bassum.

Not long after Richardis arrived at her new home, sometime around 1152, Hildegard received the news: Richardis had been struck with a sudden fever and died, never having another chance to see her best friend Hildegard or the home that she left behind.

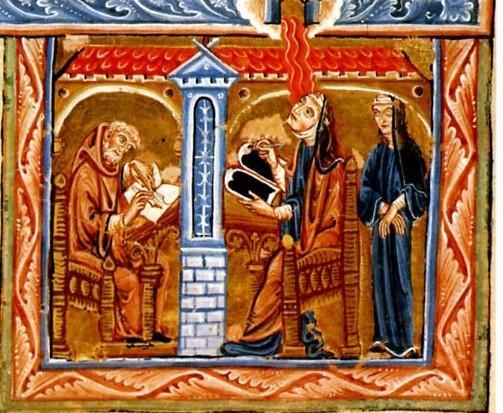

A depiction of Hildegard and Ricardis, along with Hildegard’s lifelong friend and secretary, the monk Volmar. Photo credit: Land der Hildegard

The grief of loosing Richardis would remain with Hildegard for the rest of her life. However, American Medievalist Barbara Newman believes that Hildegard’s pain did not go unexpressed. Soon after Richardis’ Death, Hildegard finished her work on the uncompleted Ordo Virtutum. The finished version tells the tale of a innocent female soul that is led astray by the devil. The Virtues then help the soul repent and find her way back home. The journey of the female soul in Ordo Virtutum parallels Richardis’ story, with the exception of there being a happy ending.

Though Richardis would never know it, in assisting Hildegard in writing Scivias and inspiring the Ordo Virtutum, she helped Hildegard solidify herself as one of history’s most important composers.

What’s clear from all of these episodes is that no composer succeeds entirely on their own. And an entire generation of classical musicians and composers are now pushing against the idea of the superhero composer as a lone genius. In Austin and beyond, musicians and artists in classical and all genres are working together to reach larger and more diverse audiences, showing us that we can all be a part of the collaborative music-making process with a little help from our friends.